“Take cover! Bring up the PIAT!” – Anthony Hopkins as Colonel John Frost of the British Parachute Regiment in the movie “A Bridge Too Far”. The issuing of that command on-screen was my first introduction to the rather odd looking, and oddly named, “Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank”, or PIAT for short.

The first light anti-tank weapons for infantrymen developed near the end of WWI and during the early inter-war period were large-calibre rifles. The British weapon in this class was the Boys Anti-Tank Rifle (nicknamed “The Elephant Gun”) which was a magazine-fed, bolt-action rifle that fired a cartridge based on the Browning .50-calibre round. The Boys Rifle proved quite useless against the latest German tanks, but it did perform well against lightly armored vehicles and fixed fortifications. It was phased out of service beginning in 1943, being replaced by the PIAT and the M2 Browning machine-gun.

But what was to take its place?

During the 1930’s, Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart Blacker of the British Army became very interested in the spigot mortar system. A spigot mortar consists of a solid rod or spigot over which a hollow tube attached to the projectile slips. The trigger mechanism is built into the base of the spigot and a long firing pin runs up the length of it to strike the primer and ignite the propellant charge that fires the projectile off the spigot. The advantages of spigot mortars are that the baseplate and spigot are smaller and lighter than conventional tube mortars of equivalent payload and range. Also, since spigot mortars don’t have a conventional barrel, a much wider range of ammunition (by weight and diameter) can be fired from the same setup. They are also simpler and easier – as well as quicker and cheaper – to manufacture.

Blacker’s original design for a platoon-level spigot mortar was rejected by the British Army, so he set about creating an anti-tank mortar, which he named the Blacker Bombard. During the dark months following the fall of France and the evacuation of the remnants of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, the British Army was desperately short of weapons and Blacker submitted his Bombard as a stop-gap solution. Although the top brass had serious doubts about the effectiveness of the Bombard, Churchill ordered it into full production after witnessing a demonstration of the weapon in August 1940.

The first Bombards appeared in late 1941, and were issued to both regular and Home Guard units up to July 1942 – by which time approximately 22,000 Bombards had been produced and issued throughout the country. It appears that some Bombards saw active service with the British Army in the Western Desert Campaign, but most were placed in fixed defensive positions around Britain. Perhaps the Blacker Bombard’s greatest claim to fame is that its design formed the basis for the Royal Navy’s Hedgehog Anti-Submarine Weapon.

The most widely-used spigot mortar system ever made, the Hedgehog Anti-Submarine Projector was developed by the Royal Navy and also used by the US and Canadian Navies. The Hedgehog fired a pattern of up to 24 projectiles ahead of a ship attacking a U-boat, and as its projectiles used contact fuses that detonated directly against the hull of a submarine it was more deadly than depth charges – which relied on damage caused by hydrostatic shockwaves.

Having seen the shortcomings and ineffectiveness of both the Boys Anti-Tank Rifle and Blacker Bombard Anti-Tank Mortar, the British Army was still desperately seeking an effective, portable, infantry anti-tank weapon by 1942. The PIAT was designed in response to this need, and also used the spigot mortar system for the propulsion of its projectile.

At the heart of the PIAT’s effectiveness however was its use of a shaped-charge warhead. The phenomenon of increasing the effective power an of explosive charge by facing a concave shape against the target went back to the so-called Monroe Effect discovered in 1888. The Monroe Effect had become effectively weaponized by the 1930s through the work of German scientists and Swiss engineers, and shaped charges were used with a devastating result by German paratroopers in their successful lightning strike against the Belgian fortifications at Eben-Emael in May 1940.

The British had also incorporated shaped charge technology in their No. 68 Anti-Tank Grenade, but the grenade too small and short-ranged to be a successful anti-tank weapon. However, when Lt.-Col. Blacker, designer of the Blacker Bombard, discovered the shaped charge technology in the No. 68 Grenade he immediately saw the potential effectiveness of a shaped charge projectile of a larger calibre – especially if it could be delivered from a handheld infantry weapon.

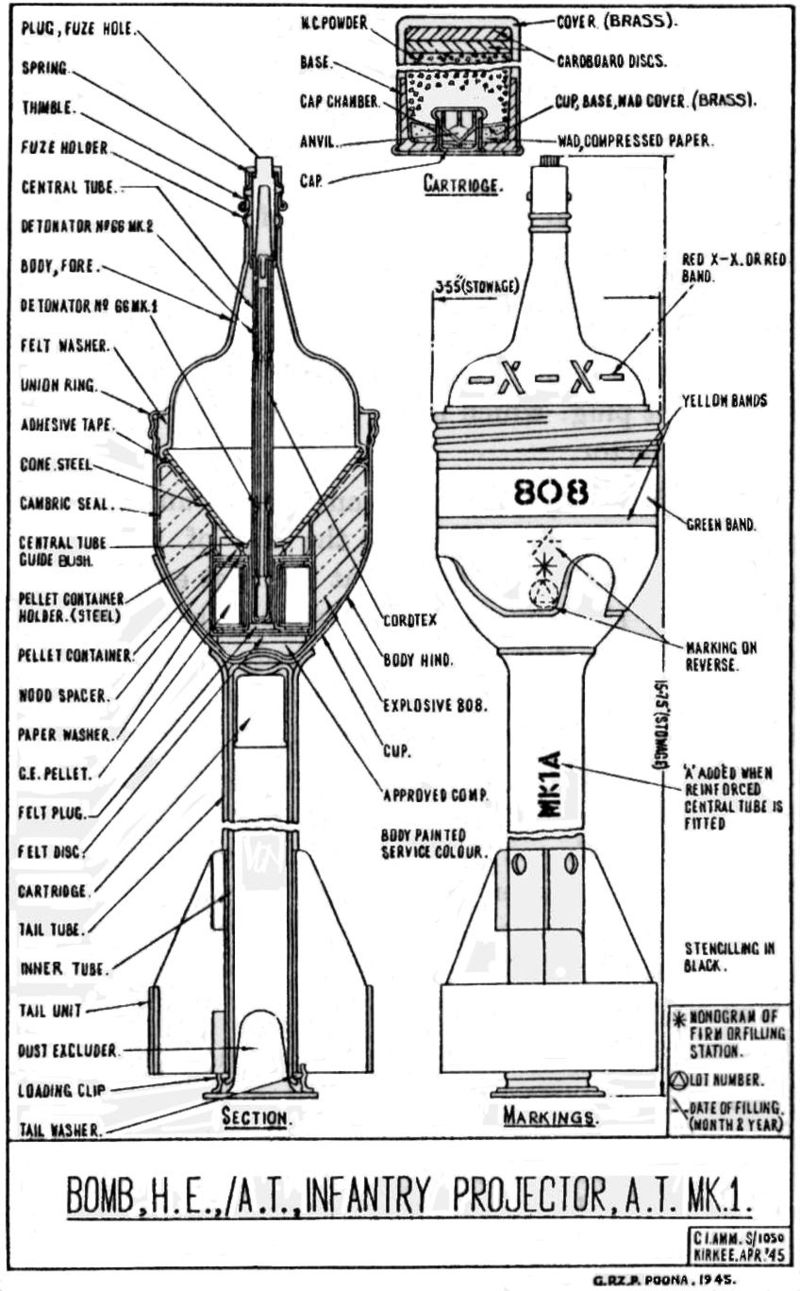

Blacker set about developing a shaped charge bomb that was fired from a shoulder-aimed launcher built around a spigot mortar system. His prototype launcher consisted of a tubular metal casing containing a large spring and a spigot, with a trough at the front where the projectile was loaded. When the trigger was pulled, the compressed spring rammed the spigot up into the tail assembly of the projectile, igniting the propellant and firing it out of the trough. The weapon, which Blacker called “The Baby Bombard”, had a range of approximately 150 yards (140 metres) and he presented it to the War Office in 1941. The War Office found a number of problems with the weapon during testing however, and the official test report in June 1941 listed such things as flimsy construction and numerous failures to fire. Most damning of all however was the fact that none of the supplied projectiles actually exploded on contact with the target.

Blacker had been posted to other duties by this time though, and so it fell to Major Millis Jefferis to try and make the Baby Bombard better. Major Jefferis had founded the organization that became known as MD1 (Ministry of Defence 1) – responsible for the design, development and production of a number of unique munitions used by British Special Forces and European Resistance units during WWII. MD1 is also known by the nickname “Winston Churchill’s Toyshop”. Major Jefferis was an explosives expert and an engineer, so was very much the right man for the job of improving on Blacker’s Baby Bombard and turning it into a functional and effective weapon of war. He took the Baby Bombard apart and rebuilt it to be more robust and reliable. He also redesigned the shaped charge mortar bomb it fired, and had a number of prototype high explosive anti-tank (HEAT) rounds constructed at “The Toyshop”. In February 1942 the resultant improved weapon , now known as the ‘Jefferis Shoulder Gun’, was ready.

Major Jefferis took the launcher and projectiles to the British Army Small Arms School at Bisley for testing. Those tests went well enough that the Ordnance Board of the Small Arms School took on the task of perfecting making the ammunition and weapon production ready – and renamed it as the ‘Projector, Infantry, Anti Tank’ (PIAT). The Ordnance Board ordered that the PIAT be issued to infantry units as a hand-held anti-tank weapon and production began at the end of August 1942.

The PIAT entered service in 1943 and could project / launch a 2.5 pound (1.1 kg) shaped charge bomb to an an effective range of approximately 115 yards (105 m) in a direct fire anti-tank role, and 350 yards (320 m) in an indirect fire role. The PIAT had several advantages over other infantry anti-tank weapons of the period; such as, greatly increased penetration power, it had no back-blast which might reveal its position or pose a danger to friendly soldiers around the user, it was inexpensive and easy to manufacture, and also simple (albeit somewhat cumbersome) to operate.

To prepare the PIAT for firing, the spring-powered spigot mechanism had to be cocked – which was a rather awkward process. First the user had to first place the PIAT on its butt, then place two feet on the shoulder padding and turn the weapon to unlock the body and lock the spigot rod to the butt. Then the user would then have to pull the body of the weapon upwards, which would draw the spring back until it latched onto the trigger. This completed the cocking the weapon. Next, the PIAT’s body would be lowered and turned to lock it back into place. Now a projectile could be placed into the trough and the PIAT was ready lob bombs at the target.

When the trigger was pulled, the spring pushed the spigot rod (with its fixed firing pin on the end) forwards and into the hollow, tubular tail assembly of bomb. This aligned the bomb, ignited its propellant charge, and launched it into the air. The recoil caused by the detonation of the propellant blew the spigot rod backwards onto the spring – automatically cocking the weapon for subsequent shots and eliminating the need to manually cock the weapon for each shot. The re-cocking of the spring also absorbed some of the recoil of the weapon – but even so it still kicked like a mule. Given the cumbersome process required to cock the PIAT, troops were trained to always carry the PIAT cocked, but unloaded, when action was expected.

Despite the difficulties in cocking and firing the weapon, the PIAT did deliver a powerful large calibre shaped charge bomb with vastly greater penetration power than anti-tank rifles – and with no muzzle blast. The PIAT also did not have any back-blast (like the American bazooka) that could endanger friendly troops or give the user’s position away. The absence of backblast and muzzle blast also meant that the PIAT could be used in the confined spaces of urban warfare. It’s powerful shaped charge warhead was also very effective for blowing “mouse holes” through walls and for taking out enemy pillboxes and other strong points.

Despite its drawbacks, the PIAT proved effective in multiple combat roles and soldiered on up through the 1950’s in the service of several nations. Six Victoria Crosses were also awarded to members of the British and other Commonwealth armed forces during WWII for action with the PIAT.

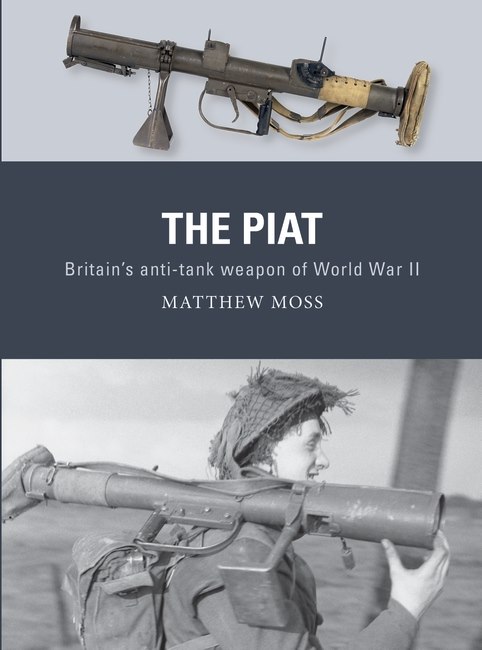

“The PIAT” is also the title of a new book in Osprey Publishing’s WEAPON series. This illustrated study combines detailed research with expert analysis to delve into the full story of the design, development and deployment of this revolutionary weapon. The author, Matthew Moss, also runs the website “Historical Firearms” and has contributed to a number of print and online publications. He is also the author of Osprey’s WPN 065 “The Sterling Submachine Gun”.