Today is the final wear-out date for the US Army’s much-maligned “Universal Camouflage Pattern” (UCP) – often incorrectly referred to as “ACU” after the Army Combat Uniform that it first appeared on – and the US Navy’s widely ridiculed “Blueberry” Navy Working Uniform Type I camouflage.

Countless comments and articles have already been published about both of these programs – and I even appeared on Fox Business once to set the record straight about UCP – so I won’t retread old ground here. Suffice it to say that the US Army’s ambition to develop a single camouflage pattern that would work in all theatres of operation was a grandiose idea to begin with, and thanks to a mistake by a General Officer it failed even harder – that is, unless you are operating in a gravel pit, or on your grandmother’s sofa…

The Navy at least didn’t try to convince the world that its sailors needed camouflage uniforms in order to hide onboard ships, instead they came up with the B.S. excuse that the pattern would help hide oil stains better. Well, so would a solid black or dark Navy blue uniform treated with Teflon. Then again, maybe there is actually a need for sailors to be able to hide onboard ship…

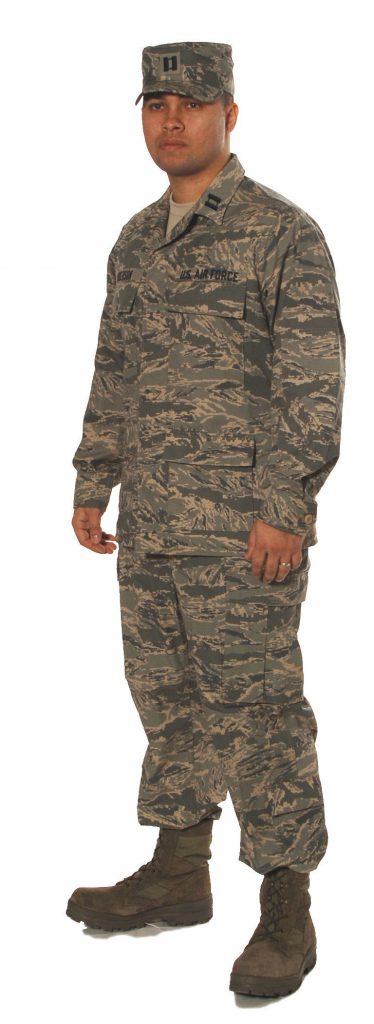

But what about that other, and perhaps most ridiculous, pattern in the triumvirate of US military camo failures? I speak of course of the US Air Force’s “digital Tiger Stripe” pattern.

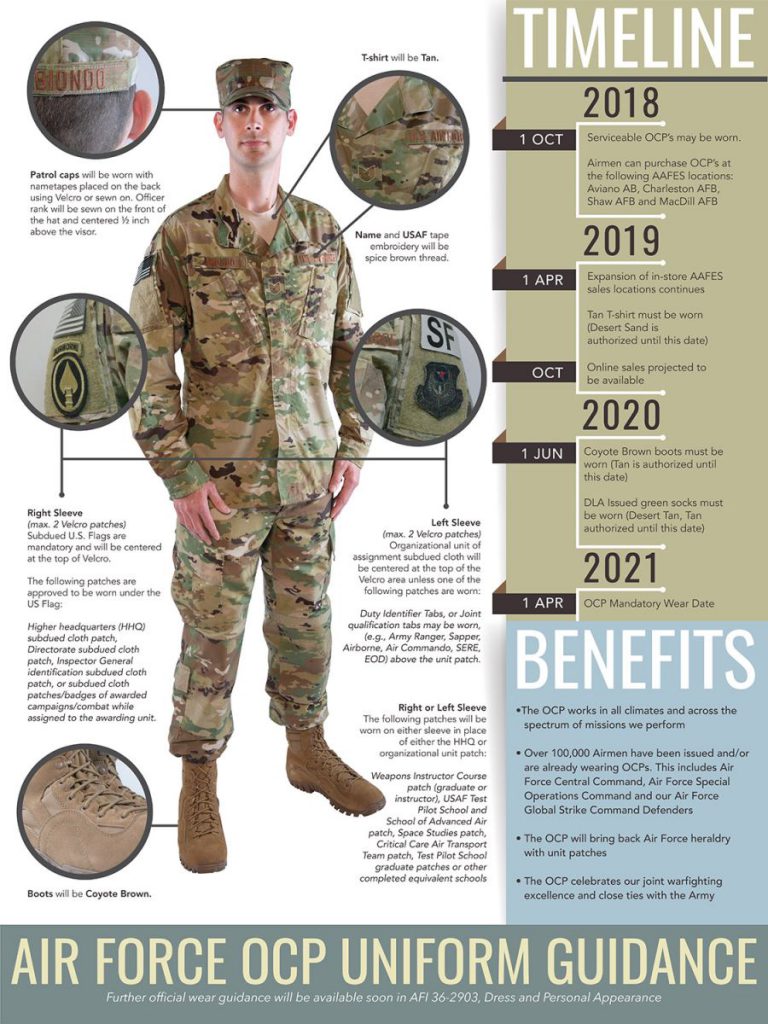

The only good thing that can be said about “Air Force Tiger Stripe” (AFTS) is that the USAF were completely honest and upfront about their intentions with it – they pretty much openly admitted that it was purely for branding and morale, and because they wanted to have a cool new camo scheme like everybody else on the playground too. Fortunately, it is also being phased out and replaced with something far more sensible.

So does this mark the end of the “digital camouflage” era? No. Digital / pixelated camouflage patterns continue to serve many nations well – including Canada, who started it all with their CADPAT pattern (upon which MARPAT, UCP, AOR 1 and 2, and NWU Type I, II, and III are all based). In fact, the Canadians are now experimenting with a new multi-terrain / intermediate version of CADPAT.

The USMC’s MARPAT woodland and desert patterns are digital patterns, as are the US Navy’s NWU Type II and III patterns for woodland / jungle and desert use – and no one seems to have any complaints about them.

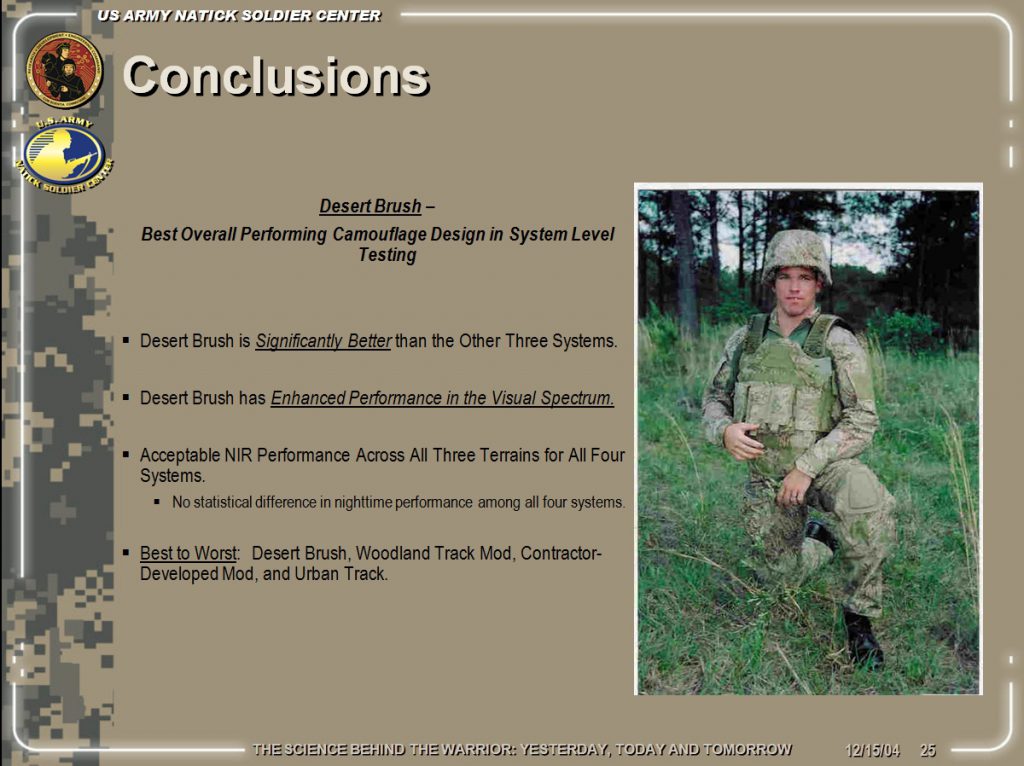

And what of the US Army’s grand ambition for a universal camouflage pattern that would work in every environment? Well of course it has been proven that no such thing is actually possible – until we can perfect an active / adaptive camouflage technology as used by the aliens in the Predator movies. The closest we can get with today’s technologies is a multi-terrain pattern that works across a wider spectrum of natural environments. Patterns that deliver this kind of capability include the “Desert Brush” pattern (sometimes referred to as “Modified Rhodesian”) that was developed by Natick Labs and actually ‘won’ the first round of analysis in their “Universal Camo” R&D program.

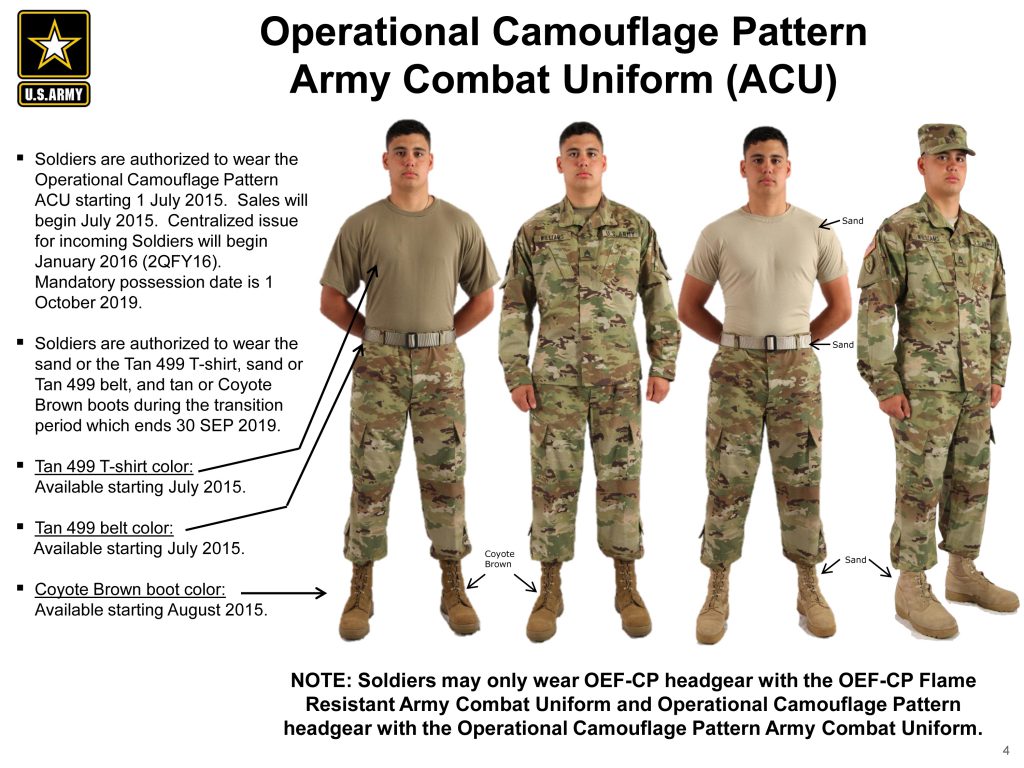

Then of course there is also Crye Precision’s famous “MultiCam” pattern that was adopted as an interim solution for use in Afghanistan. MultiCam is probably also the most successful commercial camouflage for tactical use ever developed, has spawned numerous derivatives. It also led eventually to the US Army adopting a similar pattern now known as “Operational Camouflage Pattern” (OCP) to fully replace the UCP uniforms. OCP camo ACUs have also been chosen by the Air Force to replace its digital Tiger Stripe ABU uniforms.

It has been interesting to observe the entire convoluted history of these camouflage debacles, and it has revealed a couple of things about the intersection of government and science – as well as about military procurement programs: being the best doesn’t always equal success, and sometimes national (or service) pride takes precedence over effectiveness.

Finally, in the realm of camouflage, “identity” is as important as concealment – whether that means creating a unique identity (such as MARPAT) or a shared identity (such as MultiCam and its many derivatives) – and of course the ideal outcome of course is to achieve a solution that accomplishes both objectives.