The Dutch Armed Forces are finally starting to receive new camouflage uniforms and personal equipment. But how did this come about, and what is the history of Dutch camouflage uniforms since 1945? Thanks to our friends at Dutch Defence Press we are able to bring you this exclusive English translation of an article by Major Fred Warmer – Military History Researcher, Netherlands Army.

The project to develop a new, modern and unique Dutch camouflage pattern started around 2008. The author of this article, Major Fred Warmer, was involved from early on when he was sent by the Ministry of Defense, in collaboration with TNO Defense & Security, to Afghanistan to take pictures of the environment there with a so-called color test card. From these photos a color map was developed to calibrate colors in various landscape environments.

INTRODUCTION

The road to the development of the Dutch camouflage uniform has been long, controversial and laborious.

As early as 1900, First Lieutenant of the Field Artillery A.W den Beer Poortugael published an article in the New Military Spectator in which he ardently advocated adapting the color of the uniforms to the natural environment. The armies of the neighboring countries had already preceded the Netherlands in this. So, in 1912 there was a big uniform change for the Royal Netherlands Army – the dark blue uniform and accompanying dark blue headgear, fitted with yellow copper or white metal emblems, was replaced by a gray-green uniform and headgear. Dutch military clothing had adapted to the color of the battlefield.

Over the years, Dutch military clothing was increasingly adapted to the terrain. From the original gray-green (1912) to the gray uniform (1916 – 1940); from the post-war British khaki to the American green combat clothing in the 1950s; the testing of the so-called Flecktarn pattern in the early 1980s; and finally in 1993 the introduction of the M-93 DPM and Woodland uniforms with camouflage pattern that match the colors and textures of the forests and fields of northwestern Europe – particularly the North German lowlands which is the assigned zone of 1 (NL) Army Corps.

By the time that the new NFP camouflage uniforms and equipment will be introduced by mid-2021, it will have taken 30 years to make another change.

AMERICAN CAMOUFLAGE OVERALLS

The first official camouflage uniforms for the Dutch Army were introduced in 1946 when the Expeditionaire Macht, the later Eerste Divisie ‘7 December’, was sent to the Dutch East Indies to restore order and peace. The tropical clothing, bought in haste from many countries, was inadequate and there were serious shortages of functional combat clothing. There was also no question that camouflage clothing for operations in the jungle was much needed.

A solution appeared when the Army procurement service of the KNIL discovered an enormous stock of American camouflage overalls of the M-1942 (Jungle Suit / Jungle Camouflage Coveralls) type in an American storage facility in Hollandia and Biak (New Guinea). Specially developed for combat in the Pacific, these camouflaged jungle coveralls were made of 100% cotton herringbone fabric (Herring Bone Twill) that provided excellent protection against insects and thorns, and allowed the wearer to quickly cool the body by opening the long zipper, according to the makers of the overall.

Unfortunately, they proved less than ideal in actual use. The American troops who had fought in the scorching heat of New Guinea in 1943 voiced a lot of criticism about this overall; it was too hot, too heavy, and the thick cotton fabric absorbed a lot of moisture – which made them even stiffer and more uncomfortable. The Americans had decided during the war to cease issuing overalls, which is why thousands of them ended up in storage in Hollandia, where the Dutch Armed Forces found them and took them over.

At any rate, the Dutch Armed Forces were in need of whatever equipment they could get, so the “free” American jungle overalls were sent to Java where they were first delivered to the infantry units and the Special Forces Corps (KST). But soon the Depot Special Troops (DST) and the 1st Parachute Company had specific issues regarding the camouflage overall. Furthermore, the stock of the overalls was running out and there problems with the sizes that were available. So, a Dutch version of the camouflage coverall was designed and made in Batavia for the Depot Special Troops (called the ‘Overall, Camouflage, Special Troops Model 1948’). The remainder of the batches were sent to New Guinea where the Dutch troops there carried on using them until 1955.

In the meantime, Army clothing specialists back in the Netherlands also started to think about camouflage uniforms, and came up with a new two-piece camouflage uniform consisting of a jacket and trousers – this was the so-called Lievenboom M-1950 made in Borne, Twente. The camouflage pattern was somewhat similar to the American jungle coverall, but the colors were more muted and the pattern was slightly different.

M-1950 “Lievenboom” camouflage uniform – nicknamed “Jelly Bean Pattern” by collectors. Photo credit: Defensie Uniform Prive Museum

The M-1950 camouflage uniform was introduced in 1951 (after the conflict in Indonesia had ended) and although the Korps Commandotroepen (KCT – Dutch Army Commando Corps) extensively tested them, they were ultimately not put into general issue. The uniform was not considered very practical or pleasant to wear, and the color scheme was considered to be too light for the Dutch landscape. In addition, many former resistance fighters felt that the camouflage pattern was too similar to the Waffen-SS camouflage suits from the Second World War. Eventually the uniforms disappeared into storage and were rediscovered years later, when they were used in training exercises by OPFOR units.

In 1979, a new camouflage uniform made its appearance in the Netherlands armed forces for the first time since 1955. The Dutch UNIFIL (United Nations Interim Force In Lebanon) detachment from 1979-1985 was issued with a camouflage rain suit in a black, brown, green and ocher-yellow camouflage pattern that was nicknamed the “Jigsaw pattern”. After the cessation of participation in UNIFIL, the remaining suits were used up by reconnaissance units, EOD and the Netherlands Army Graves Unit.

COMBAT PSU 80 PROJECT

In the meantime, a ‘Working Group Combat PSU’ had been set up in 1972, which had the task of considering all articles belonging to the combat PSU of the military, in order to be assemble an adequate combat PSU for issue by 1980. The project group was also instructed to develop new camouflage uniforms for the armed forces in cooperation with other NATO partners that would be suitable for use by the 1st Army Corps (1 LK) in the North German lowlands.

In 1982 the Equipment Supply Department (MVA) 6 started the project of developing a new camouflage suit. Together with TNO (Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research) and the Twente textile company Nijverdal-Ten Cate, they developed a camouflage combat suit that was executed in the German-developed Flecktarn pattern. However, this project was delayed because, in view of the British experiences during the Falklands crisis (March / June 1982), the suits also had to be made of strong fire-resistant fabric, which again conflicted with the application of the newly designed camouflage pattern.

It took until September 1985 before soldiers of the 13th Armored Brigade in Oirschot started testing this new camouflage combat clothing in practice. The intention was to introduce the new outfit for the entire army from 1988. The camouflage pattern, developed by the German Firm Marquadt & Schulz, had already been adopted by the Bundeswehr and was seen as being extremely effective for use in the North German / North Sea area lowlands. In fact, evaluations and testing by the TNO and the Camouflage School in Reek had scientifically established that the German Flecktarn camouflage was by far the best camouflage available at the time.

However, protests by former resistance fighters again resurfaced in the media. In their eyes, the camouflage suit again looked too much like the hated Waffen-SS camouflage suits from the Second World War, especially in combination with the new Kevlar helmet that had a similar shape to the WWII German Stahlhelm.

Meanwhile, there was also a lot of opposition within the Armed Forces, especially from units and soldiers who were not allowed to wear the new uniform during the trial period. So, even though intensive testing of the camouflage pattern and various styles of garments had taken place, the plan to introduce the new “Stippel” camouflage clothing was abandoned in 1987. Several reasons were cited for taking this decision, including;

- users liked the pattern to wearing a “floral wallpaper suit”

- there were complaints about double vision when looking at the “dot pattern” for a long time

- there were also many complaints about the freedom of movement in the jacket and the poor quality of certain textiles

- the fabric apparently felt “lifeless” after a while and also shrunk too much

- the long parka and body warmer were perceived as a nuisance, and the Velcro closures made too much noise, which was felt would alert the enemy during nighttime operations

- Finally, there was controversy in the media over the comparison with the Waffen-SS camouflage uniform in WWII

The Flecktarn pattern does indeed show some influence from the “spotty” camouflage pattern used by the Waffen-SS in World War II, but the Wehrmacht and W-SS also used dozens of other, different-looking camouflage patterns at the time as well. With an objective view, it can in fact be said that the German camouflage designers of the 1940s were far ahead of everyone else in this field, and established principles that have influenced many of the best camouflage designs of the last century.

COMBAT CLOTHING M-93

At the end of August 1988, new mock-ups for the combat PSU were presented, that now featured a redesigned ‘brushstroke’ camouflage pattern, based on the UK’s Disruptive Pattern Material (DPM). This pattern used smudged streaks instead of dots, and had a clearly different color scheme.

However, this introduction did not proceed without a struggle either. With arguments such as “within Dutch society camouflage uniforms would be considered too aggressive”, opponents, both inside and outside the Armed Forces, tried to sabotage the introduction.

Nonetheless, in 1992, after years of deliberation and political scheming, the new combat clothing and equipment entered service as the M-93 system. There were three varieties: woodland, desert and tropical. These suits have been expanded over the years in terms of clothing and equipment, but the basic pants, jacket and parka designs are still worn by the Netherlands Armed Forces to this day.

Editor’s note: Although the British-style DPM camouflage pattern and new style combat/field uniforms were adopted as the new standard-issue for the Royal Netherlands Army and Air Force, Netherlands Marine Corps (Korps Mariniers) in 1993 opted for the US M81 Woodland camouflage pattern executed on a close copy of the US Battle Dress Uniform style. A near copy of the US 3-Color Day Desert camouflage pattern was also selected for arid region uniforms by the Korps Mariniers, as well as the rest of the Dutch Armed Forces.

SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES

The Special Operations Forces of the Netherlands have introduced and used a wide variety of new uniforms and equipment since 1992. The purchase and implementation of which is completely autonomous and separate from the broader, standard-issue developments. These purchases are also funded from other means than the regular units. This leaves more room for innovations and quick purchases of necessary specialist clothing and equipment.

During the missions in Afghanistan (TF Viper and TF 55) and Iraq, MultiCam uniforms were worn and during the participation of the KCT in the SOLTG mission in Mali, so-called ‘Fightex’ camouflage uniforms were used that were specially designed and developed by the Israeli firm Fibrotex and supplied by the Dutch company Profile Equipment. These flame retardant garments were selected because they are more suitable for the dangers poised by IEDs and the extreme heat in the Malian desert.

Around the end of the second decade, after collaboration between the Interservice Knowledge Center Special Operations (IKCSO), the Matlogco and the industry, including the aforementioned Profile Equipment, a new combat outfit with the MultiCam pattern was introduced – after testing uniforms from various manufacturers and suppliers.

In addition, units of the SOCOM, the Marine Corps and the Army have also been equipped with a new model Fightex jungle uniform, which, like the arid version, was developed by the Israeli company Fibrotex and adapted to the needs of the Dutch military by the company Profile Equipment.

DEFENSE OPERATIONAL CLOTHING SYSTEM

As part of the DOKS (Defense Operational Clothing System), the Netherlands Armed Forces were due to get a completely new uniform system between 2020 and 2022, but the delivery has been delayed due to various circumstances. As early as 2017, the project experienced its first delays, after which the then CDS, Lieutenant Admiral Bauer, via DMO and the NSPA, ordered 7,200 interim combat suits in the “MultiCam pattern” for operations abroad. MultiCam is a camouflage design from the US company Crye Precision that was designed for use in a wide range of terrain conditions, and the uniforms were quickly purchased ‘off-the-shelf’ through the NSPA in Luxembourg.

DEVELOPMENT OF NETHERLANDS FRACTAL PATTERN CAMOUFLAGE

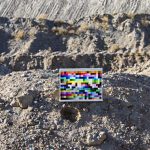

In 2008, various defense photographers were sent around the world by the Ministry of Defense in collaboration with TNO Defense & Security to take pictures with a so-called color test chart. This color test chart served to calibrate colors in various landscape environments, under various lighting conditions and at various times. TNO made so-called color histograms of these photos by determining how often colors occur in a certain environment. Digital computer technology crystallized the color / camouflage pattern that best matched clothing and equipment. And with good results it now appears. Comparative tests with existing global patterns show that the new Netherlands Fractal Pattern (NFP) works very well in various environments and under varying circumstances.

In fact, every environment requires a separate camouflage pattern. However, that is not practical and logistically and financially unfeasible. Endless patterns would arise and the soldier would even have to carry several uniforms at the same time during a deployment. The aim is to use as few patterns as possible with maximum results.

For combat clothing, the Netherlands Fractal Pattern (NFP) has provisionally been established in 3 variants for different ‘theaters of performance’, plus a fourth, mixed-pallet version for all individual equipment:

- NFP-Green for wooded and urban areas in Western and Eastern Europe

- NFP-Tan for arid regions such as deserts, steppes and savannas

- NFP-Navy for Navy crew

- NFP-Multitone for individual load-carrying and protective equipment

- NFP-Arctic for winter / mountain conditions – still being considered

INTERIM COMBAT CLOTHING IN NFP CAMOUFLAGE

The aforementioned problems meant that the new, and definitive clothing, would not be delivered until mid-2023/24 at the earliest, and it was therefore decided to deliver a provisional, but improved, interim clothing package in the NFP camouflage pattern. This standard-issue interim combat clothing ensemble is based on the current BDU-style combat trousers and jacket of the Netherlands Marine Corps, but is printed with the new “Netherlands Fractal Pattern (NFP)” camouflage pattern. The exact composition of the package rollout is currently being coordinated with all components of the Netherlands Armed Services, including; the Koninklijke Landmacht (Royal Netherlands Army), the Koninklijke Luchtmacht (Royal Netherlands Air Force), the Koninklijke Marechaussee (Royal National Police), and the Korps Mariniers (Netherlands Marine Corps) – all of which are expected to adopt the new NFP uniforms and gear. The Navy will also receive a new on-board ensemble, to replace the current blue outfit, which will feature a unique blue-colored version of the NFP camouflage pattern.

NETHERLANDS FRACTAL PATTERN EQUIPMENT

Equipment such as backpacks is made from stiffer fabrics than clothing. Those coarser fabrics are difficult to print with the fine pattern NFP Green that is used on the clothing. In addition, most equipment should be able to be used in all deployment areas, again for logistical and financial reasons. Thus a slightly coarser and simpler pattern was created, NFP-Multitone, consisting of fewer colors and a little more contrast. It also contains the colors from both NFP-Green and NFP-Tan to make it functional for both verdant and arid environments.

The development of new combat equipment to compliment the new operational clothing has been implemented within the “Individual System Soldier” (ISS) procurement project. ISS includes the Improved Operational Soldier System (VOSS), which will cover the equipment for all soldiers of dismounted combat units.

The VOSS equipment, includes a new helmet from the Galvion company (formerly Revision Military) and the SMART vest developed by the Israeli companies Elbit and Marom Dolphin. Testing and implementation of this new equipment has been managed by the STRONG project – STRONG stands for Soldier TRansformation ONGoing. Within this project, the individual soldier receives an equipment package that is tailored to his function within a specific unit with a specific task. For example, an armored infantryman will receive different equipment than the driver or soldier of a recovery unit. When all is said and done, every member of the Netherlands Armed Forces will receive a standardized set of clothing and equipment that is also tailored to their individual role requirements.

Editorial note: A more detailed look at the typical equipment being issued can be found at Joint-Forces.com

POSITIVE MORALE INFLUENCE OF FUNCTIONAL PGU

It has become clear in recent years that a good-looking and functional combat suit, which will put the Dutch military on par with various foreign coalition partners, has a significant positive influence on the mental component of the military. A uniform and equipment with a professional appearance reflects a professional soldier and creates both better presentation and performance. That’s how soldiers want to be seen when they are deployed. Good clothing and equipment has a direct influence on morale, and with it the performance of our soldiers.

Having sat on the sidelines of international developments in the fields of camouflage, textiles, clothing designs, and equipment innovation for almost 40 years, the decision-makers in defense have either completely ignored or seriously underestimated the importance of this critical component of defense. This is despite the fact that such knowledge was widely available, and that there was constant feedback from Dutch military personnel deployed to areas where they would feel themselves poorly equipped compared to even smaller and less wealthy coalition countries. Partly for this reason, individual soldiers, and complete units up to company level, would often spend their own money to independently purchase clothing and equipment to make up for the shortcomings in their issued gear.

It should not be forgotten that draconian defense cuts made since 1992 by various cabinets – in the misguided belief that they would benefit from a so-called “peace dividend” – is largely to blame for neglecting this vital component of defense policy. This has left Dutch soldiers short-changed with regards to their clothing and equipment despite being continuously deployed abroad on various missions to dangerous areas around the world that had never heard of a peace dividend.

Even now, due to the various and lengthy delays in the development and implementation of the ambitious new combat clothing and equipment projects, confidence in the political will to uphold this side of defense policy has been seriously diminished. It is hoped that diligently rolling-out of the interim combat clothing and the rest of the ISS equipment will restore some of that lost confidence.

Original version of this article (in Dutch language) can be seen here. Our sincerest thanks to Gerard at Dutch Defence Press, and Major Warmer, for their kind permission to translate and publish this article in English.

English translation and editing by Lawrence Holsworth.

Photos, unless otherwise noted: Defense image bank / NIMH, MCD, photo archive HCKNR, Major Fred Warmer