The “Winter War” between little Finland and the mighty Soviet Union began on this date eighty-one years ago.

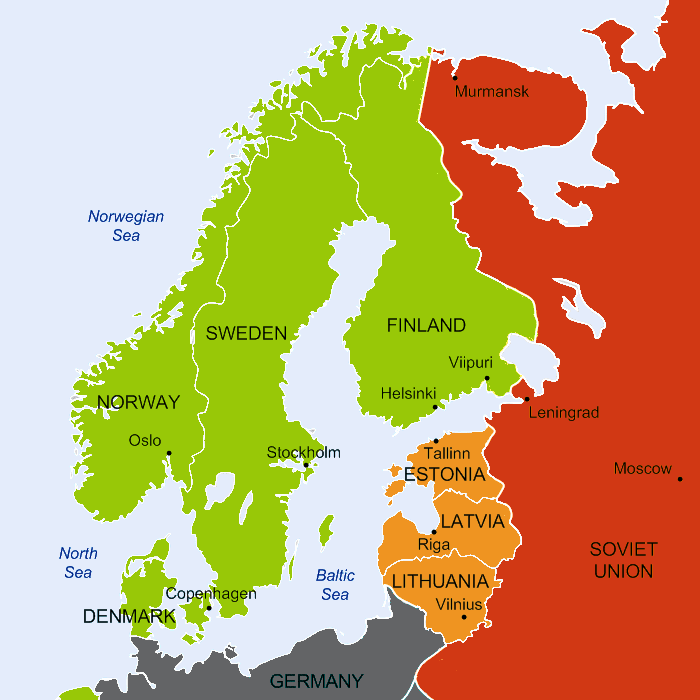

With Britain and France preoccupied with preparing themselves for war against Nazi Germany, and with the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact in place to protect their flank, the Soviets thought that they could safely and swiftly conquer Finland – and re-establish historical Russian dominance of the Baltic Sea.

It is also worth bearing in mind that Finland had only become recognized as a nation independent from the Russian Empire in January of 1918, following the the overthrowing of the Tsar and the Bolshevik Revolution in October/November 1917. The 1920’s and ’30’s were a turbulent time in Finnish / Russian relations, with territorial disputes, tensions between the new nation and its ethnic Russian minority, and internal political agitation and armed conflict between nationalist and communist movements. When Stalin became the supreme leader of the Soviet Union in 1938 he adopted a hard-line policy towards Finland that made clear his desire to reabsorb the country into the Soviet sphere of control.

The secret terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939 granted the Soviet Union a free hand to establish controlling influence over the eastern half of Poland, as well as the Baltic States and Finland. The Soviets invaded eastern Poland on the 17th of September 1939 and used their presence there to put pressure on Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The Finns however resisted several Soviet demands for influence and territory, and ultimately rejected any possible compromise that would cost them their independence, sovereignty or territory.

On 26 November 1939 the Soviet NKVD (predecessor to the KGB) staged a false-flag operation against a Soviet border post – through the means of an artillery barrage. The Soviets blamed the attack on the Finns and in return demanded an apology and the withdrawal of all Finnish forces 25km back from the border. The Finns, who had no artillery units anywhere within range of the border post, refused to cooperate and denied any involvement with the incident. In response, 21 divisions of the Soviet Army (totalling 450,000 men) poured across the border with Finland on the 30th of November 1939.

The Soviets also bombed Helsinki on the same day, causing a great many casualties and much destruction. In response to the international outcry over the bombing of civilians, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov claimed that the Russian planes were dropping bread to the starving citizens of Helsinki. With their typical deadpan humor the Finns in turn nicknamed the Russian bombs breadbaskets, and gave the flaming petrol bombs they used against Soviet tanks the nickname “Molotov Cocktails”.

The Red Army however soon learned that the Finnish forces were no joke, and that this little country on the northern tip of Europe was not going to be so easy to conquer after all. Despite their vast superiority in numbers the Red Army was not very well equipped or trained, and Stalin’s purges had also decimated the officer ranks. The well-educated, highly-trained, and combat-hardened professional soldiers of pre-Soviet Russia were gone – replaced by one’s who were considered more politically correct and loyal to Stalin. Although the Soviets were able to persevere in some areas due to their sheer numbers, the overall result was catastrophic for the reputation of the Red Army.

The Soviets, in their khaki uniforms and olive green vehicles, operated in large size elements moving methodically along open avenues of approach according to set battle plans. The Finns on the other hand would emerge from their well-camouflaged defensive positions and move swiftly and silently through the frozen forests on skis – they also wore white capes and overalls to camouflage them against the deep snow. Like packs of wolves, the Finns would suddenly emerge out of the gloom and sweep in among the Russian forces, disrupting their formations and dividing them into smaller elements that they could then destroy piecemeal. Finnish snipers, such as the famed “White Death” Simo Häyhä, would also lie in wait perfectly camouflaged in the snow and pick off Russian commanders, crew-served weapons gunners, and other targets of opportunity – without ever revealing their positions.

Despite the tactical success of their ski troops and guerrilla tactics though the Finns had neither the manpower nor materiel to fight a drawn-out war of attrition. The Soviet Union however could certainly muster enough of each to eventually grind down the Finnish resistance. By mid-February the Finnish forces were nearing exhaustion, the Soviets were keen to wrap things up before the spring thaw turned all the roads to impassable mud bogs – or the British and French were able to get an intervention force organized to help the Finns. The Swedish and German governments were also eager for the war to end – for reasons of their own. And so, reluctantly, the Finns entered into negotiations with the Soviet Union.

By the beginning of March 1940 the situation of the Finnish forces was becoming critical and the country also found itself alone and isolated internationally. So, unable to avoid the inevitable any longer, the Finnish President signed a peace treaty with the Soviet Union in Moscow on 12 March 1940. Under the terms of the so-called “Moscow Peace Treaty” Finland lost 11 percent of its territory and 30 percent of economic assets – adding insult to injury, the economic concessions and territorial losses actually exceeded the demands the Soviets had made before the war.

Although often forgotten and overlooked, the Winter War had ramifications that reached beyond the 105 days of its duration – and beyond the borders of Finland as well. Perhaps most significantly, the poor performance of the Russian Army convinced Hitler that an invasion of the Soviet Union would bring about the swift and total collapse of the Red Army at the hands of the well-trained, well-equipped, and professionally-led Wehrmacht. The Winter War also proved that the League of Nations was totally powerless and ineffectual, and that the Anglo-French Supreme War Council was equally weak and ineffective and not up to the task required of it – which brought about the downfall of the government in France.

Last, but not least, the unsatisfactory end of the Winter War left a lingering thirst for vengeance against the Soviet Union among influential elements of the Finnish government. This, as well as other extenuating circumstances and provocations, led Finland to ally itself with Nazi Germany in the invasion of the USSR in June 1941. On the Finnish side this became known as the Continuation War and lasted from June 1941 to September 1944.

Further reading:

“Finnish Soldier vs Soviet Soldier – WINTER WAR 1939–40”, Osprey Publishing