On November 21, 1970 – 50 years ago this past weekend – a milestone event in the history of Special Operations Forces took place. This was “Operation Ivory Coast” – the Son Tay Prison Raid – which is sadly often overlooked and forgotten outside of the US Special Operations Community.

By 1970 the US had been directly involved in the Vietnam War for over a decade and a half with no end in sight. In the US, opposition to the war was at an all time high and the polarization of the issue was literally tearing the country apart. Richard Nixon had won the US Presidential election in 1968 on the back of promising to end the draft, restore law and order, and bring about an “honorable end” to the war in Vietnam.

However, that promised “honorable end” still looked like a distant dream though by the spring of 1970 – even though Henry Kissinger, US Secretary of State, had already begun having secret meetings in Paris with high level representatives of the North Vietnamese government. Meanwhile, the treatment and fate of U.S. prisoners of war in Vietnam had also become a subject of widespread concern in the United States. The vast majority of these POWs were Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps flying officers, and it was widely known that the North Vietnamese were subjecting them to torture, malnutrition, and inhumane living conditions. The goal of the North Vietnamese was not to extract useful military intelligence, it was simply to break their spirit and to coerce them into making statements condemning the US and praising the North Vietnamese. Their aim was to use such propaganda to sew dissent and demoralization among the US ranks and to influence the civilian population even further in political opposition to the war.

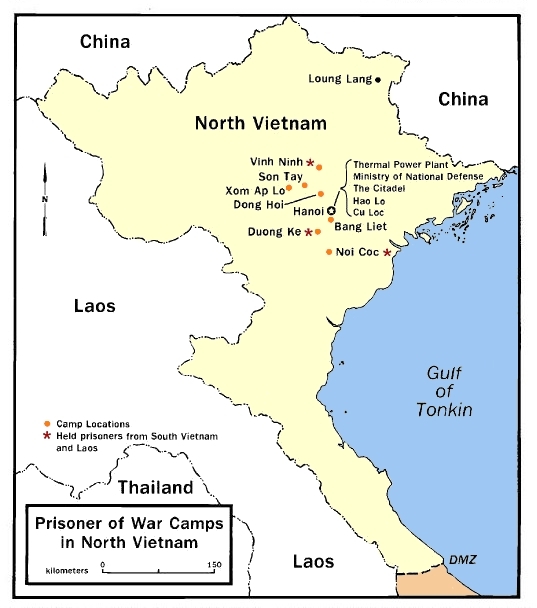

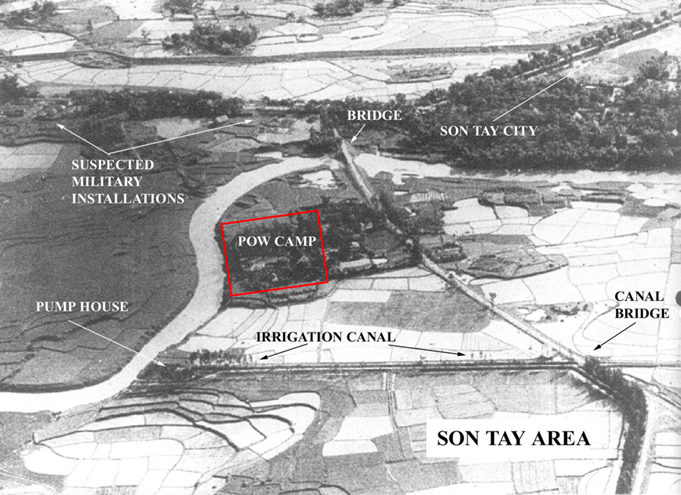

Against this turbulent backdrop, the US military had identified and located numerous prison camps in North Vietnamese territory where US POWs were being held. Beginning in May 1970 the concept of planning for a POW rescue operation got underway, when extensive analysis of Air Force aerial photographs identified a North Vietnamese prison camp near Sơn Tây that appeared to hold approximately 60-65 Americans – several of whom seemed to be in need of urgent medical care. Planning was authorized by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and was undertaken jointly by Air Force Brigadier General LeRoy J. Manor and Army Colonel Arthur D. “Bull” Simons – under the codename “Operation Ivory Coast”.

Gen. Manor set up a training facility at Eglin’s Duke Field and brought together his planning staff, while Col. Simons recruited personnel from the 6th and 7th Special Forces Groups at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In all, 103 Army and 116 Air Force personnel were selected, including ground force members, aircrew, support groups, and planners – the task force planned, trained, and operated under the title of the “Joint Contingency Task Group” (JCTG).

Planning took place throughout the month of August 1970, while air and ground training began in early September. Ground training for the mission was carried out at a remote range on featuring a complete, full-size replica of the prison compound, and a detailed five-foot-by-five-foot scale table model. During the month of October extensive, several full-scale dress rehearsals – some involving live firing – took place involving all air and ground elements of the planned mission, running from start to finish. One of the key outcomes of such detailed training and rehearsing was the realization that the ubiquitous UH-1 “Huey” helicopter was not up the task and the larger HH-53 “Jolly Green Giant” was selected for the mission instead.

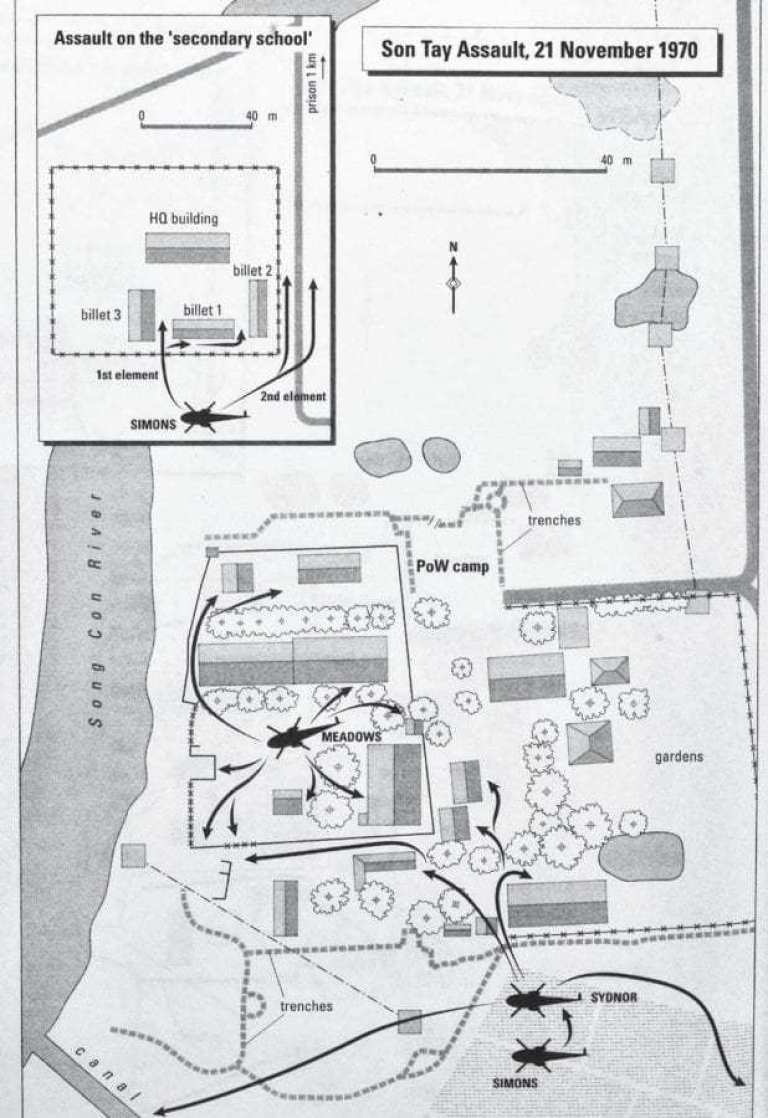

The Special Forces ground element was organized into three platoons: a 14-man assault group (codenamed Blueboy); a 22-man immediate support group (codenamed Greenleaf), and a 20-man perimeter security / backup group (codenamed Redwine). These 56 raiders were heavily armed with CAR-15 carbines, M16 rifles, M79 grenade launchers, shotguns, M60 machine guns, Claymore mines, demolition charges, and hand grenades. They were also equipped with a wide range of additional tools and equipment including wire and bolt cutters, axes, chainsaws, crowbars, ropes, bullhorns, and lights to assist with freeing and marshaling the POWs for rescue. The ground force was also equipped for voice communications with UHF and VHF radios, as well as an individual survival radio for each man.

The formal launch order for the mission was given at 15:56 local time 20 November 1970, and at 02:19 hours local time on 21 November 1970 the HH-3E helicopter (callsign ‘Banana’) carrying the Blueboy assault force landed in the courtyard of the Son Tay prison complex. The assault force debussed from their helicopter, immediately fanned out into 4 elements and began an aggressive attack on the prison – killing every guard they happened upon, while also rapidly but methodically searching every cell block for prisoners.

After two thorough searches of the camp, the raiders determined that there were in fact no prisoners being held there at that time and the extraction command was passed through to the waiting HH-53 helicopters. The assault force and two support elements were all back onboard, accounted for, and in the air by 02:48 hours – less than half an hour after the assault force had landed. By 03:15 they had cleared North Vietnamese territory and by 04:28 they were back on the ground at Udorn AFB in Thailand.

Although the Son Tay raid was considered a militarily tactical success from a planning, training and execution perspective, it was resoundingly condemned as a failure, an embarrassment and an endangerment to the treatment of American POWs by Nixon’s political opponents, and by the Vietnam War protest movement. Even within the military, it was widely seen as an intelligence failure.

Information had been received from a usually reliable North Vietnamese source on 19 November that the Son Tay prisoners had been moved to a different camp on the 14th of July – due to the wells at Son Tay becoming contaminated from flooding in the area. However, due to the compartmentalization in which intelligence was analyzed, processed, and shared this information did not become known to the senior commanders in Washington D.C. until only a few hours before the mission was due to launch. As there was no confirmation of this 4-month old information from a single source, the decision was taken to proceed as planned.

While the raid failed to free any POWs, it did have several positive implications for American POWs. The most immediate result was a massive improvement in the morale of the POWs knowing that the US government was actively attempting to rescue and repatriate them. On the North Vietnamese side the effect was immediate as well – American prisoners in North Vietnam were all moved to Hỏa Lò Prison in downtown Hanoi. For the first time in months, many of the prisoners now had cell mates to talk to, they were allowed extra recreational activities, and food, medical care, and mail delivery all improved after the raid too. This great improvement in their conditions led the Americans to nickname the prison “The Hanoi Hilton”.

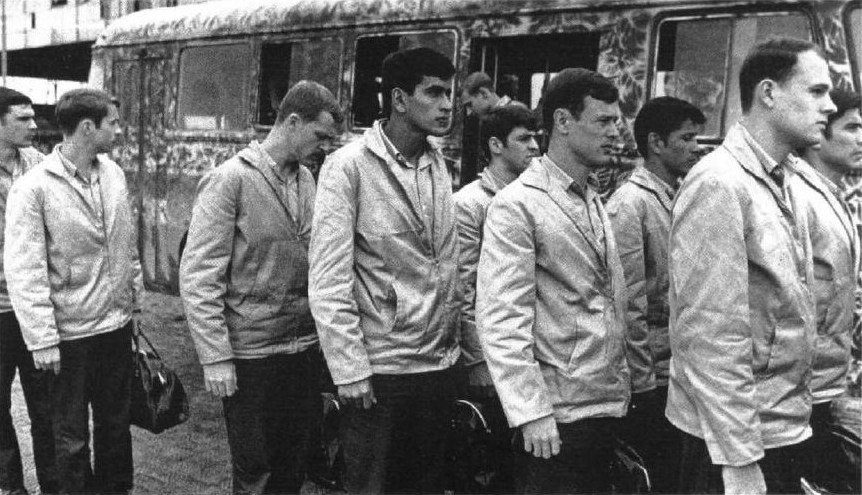

On 27 January 1973 President Nixon signed the Paris Peace Accords, establishing a cease-fire with North Vietnam and officially ending direct US military involvement in the Vietnam War. From February through April 1973 the North Vietnamese released 591 acknowledged US prisoners of war during “Operation Homecoming” – although controversy has continued ever since as to whether the North Vietnamese accurately accounted for all American POWs, and also whether they did in fact repatriate them all.

Despite the tatical success of the mission, and its planning and training, no effort was made to institutionally preserve the experience and lessons learned by command task force, nor its procedures for enabling national level command authority over high value operations. The willingness – if not eagerness to sweep aside the memory of the operation was perhaps due to the bitter and lingering criticisms of it.

It would take a second major national embarrassment and military failure at a remote desert site in Iran 10 years later – as well as issues with operations in Grenada in 1983, Panama in 1989, and Somalia in 1993 – before a unified U.S. Special Operations Command would be established and fully capable to plan, train, and execute joint special operations across the world. A process that ultimately paid dividends when Osama Bin Laden, architect of the 9/11 attacks on New York City and Pentagon, was tracked to and eradicated from his hideaway deep inside Pakistan on 2 May 2011.

——

Be sure to check out the Son Tay Raid Association on Facebook, as well as this article about the 50th Anniversary Commemoration Event on Soldier Systems Daily. A very good write-up about the mission also appeared in the 2020 Edition of Special Operations Outlook.